History Will Tell (reprint from Vanity Fair)

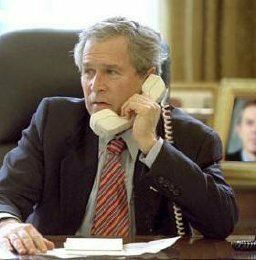

The History Boys

In the twilight of his presidency, George W. Bush and his inner circle have been feeding the press with historical parallels: he is Harry Truman—unpopular, besieged, yet ultimately to be vindicated—while Iraq under Saddam was Europe held by Hitler. To a serious student of the past, that's preposterous. Writing just before his untimely death, David Halberstam asserts that Bush's "history," like his war, is based on wishful thinking, arrogance, and a total disdain for the facts.

by David Halberstam August 2007

We are a long way from the glory days of Mission Accomplished, when the Iraq war was over before it was over—indeed before it really began—and the president could dress up like a fighter pilot and land on an aircraft carrier, and the nation, led by a pliable media, would applaud. Now, late in this sad, terribly diminished presidency, mired in an unwinnable war of their own making, and increasingly on the defensive about events which, to their surprise, they do not control, the president and his men have turned, with some degree of desperation, to history. In their view Iraq under Saddam was like Europe dominated by Hitler, and the Democrats and critics in the media are likened to the appeasers of the 1930s. The Iraqi people, shorn of their immensely complicated history, become either the people of Europe eager to be liberated from the Germans, or a little nation that great powerful nations ought to protect. Most recently in this history rummage sale—and perhaps most surprisingly—Bush has become Harry Truman.

Illustrations by Edward Sorel.

We have lately been getting so many history lessons from the White House that I have come to think of Bush, Cheney, Rice, and the late, unlamented Rumsfeld as the History Boys. They are people groping for rationales for their failed policy, and as the criticism becomes ever harsher, they cling to the idea that a true judgment will come only in the future, and history will save them.

Ironically, it is the president himself, a man notoriously careless about, indeed almost indifferent to, the intellectual underpinnings of his actions, who has come to trumpet loudest his close scrutiny of the lessons of the past. Though, before, he tended to boast about making critical decisions based on instinct and religious faith, he now talks more and more about historical mandates. Usually he does this in the broadest—and vaguest—sense: History teaches us … We know from history … History shows us. In one of his speaking appearances in March 2006, in Cleveland, I counted four references to history, and what it meant for today, as if he had had dinner the night before with Arnold Toynbee, or at the very least Barbara Tuchman, and then gone home for a few hours to read his Gibbon.

I am deeply suspicious of these presidential seminars. We have, after all, come to know George Bush fairly well by now, and many of us have come to feel—not only because of what he says, but also because of the sheer cockiness in how he says it—that he has a tendency to decide what he wants to do first, and only then leaves it to his staff to look for intellectual justification. Many of us have always sensed a deep and visceral anti-intellectual streak in the president, that there was a great chip on his shoulder, and that the burden of the fancy schools he attended—Andover and Yale—and even simply being a member of the Bush family were too much for him. It was as if he needed not only to escape but also to put down those of his peers who had been more successful. From that mind-set, I think, came his rather unattractive habit of bestowing nicknames, most of them unflattering, on the people around him, to remind them that he was in charge, that despite their greater achievements they still worked for him.

He is infinitely more comfortable with the cowboy persona he has adopted, the Texas transplant who has learned to speak the down-home vernacular. "Country boy," as Johnny Cash once sang, "I wish I was you, and you were me." Bush's accent, not always there in public appearances when he was younger, tends to thicken these days, the final g's consistently dropped so that doing becomes doin', going becomes goin', and making, makin'. In this lexicon al-Qaeda becomes "the folks" who did 9/11. Unfortunately, it is not just the speech that got dumbed down—so also were the ideas at play. The president's world, unlike the one we live in, is dangerously simple, full of traps, not just for him but, sadly, for us as well.

When David Frum, a presidential speechwriter, presented Bush with the phrase "axis of evil," to characterize North Korea, Iran, and Iraq, it was meant to recall the Axis powers of World War II. Frum was much praised, for it is a fine phrase, perfect for Madison Avenue. Of course, the problem is that it doesn't really track. This new Axis turned out to contain, apparently much to our surprise, two countries, Iraq and Iran, that were sworn enemies, and if you moved against Iraq, you ended up de-stabilizing it and involuntarily strengthening Iran, the far more dangerous country in the region. While "axis of evil" was intended to serve as a sort of historical banner, embodying the highest moral vision imaginable, it ended up only helping to weaken us.

Despite his recent conversion to history, the president probably still believes, deep down, as do many of his admirers, that the righteous, religious vision he brings to geopolitics is a source of strength—almost as if the less he knows about the issues the better and the truer his decision-making will be. Around any president, all the time, are men and women with different agendas, who compete for his time and attention with messy, conflicting versions of events and complicated facts that seem all too often to contradict one another. With their hard-won experience the people from the State Department and the C.I.A. and even, on occasion, the armed forces tend to be cautious and short on certitude. They are the kind of people whose advice his father often took, but who in the son's view use their knowledge and experience merely to limit a president's ability to act. How much easier and cleaner to make decisions in consultation with a higher authority.

Therefore, when I hear the president cite history so casually, an alarm goes off. Those who know history best tend to be tempered by it. They rarely refer to it so sweepingly and with such complete confidence. They know that it is the most mischievous of mistresses and that it touts sure things about as regularly as the tip sheets at the local track. Its most important lessons sometimes come cloaked in bitter irony. By no means does it march in a straight line toward the desired result, and the good guys do not always win. Occasionally it is like a sport with upsets, in which the weak and small defeat the great and mighty—take, for instance, the American revolutionaries vanquishing the British Army, or the Vietnamese Communists, with their limited hardware, stalemating the mighty American Army.

There was, I thought, one member of the first President Bush's team who had a real sense of history, a man of intellectual superiority and enormous common sense. (Naturally, he did not make it onto the Bush Two team.) That was Brent Scowcroft, George H. W. Bush's national-security adviser. Scowcroft was so close to the senior Bush that they collaborated on Bush's 1998 presidential memoir, A World Transformed. Scowcroft struck me as a lineal descendant of Truman's secretary of state George Catlett Marshall, arguably the most extraordinary of the postwar architects of American foreign policy. Marshall was a formidable figure, much praised for his awesome sense of duty and not enough, I think, for his intellect. If he lacked the self-evident brilliance of George Kennan (the author of Truman's Communist-containment policy), he had a remarkable ability to shed light on the present by extrapolating from the the past.

Like Marshall, I think, Scowcroft has a sense of history in his bones, even if his are smaller lessons, learned piece by piece over a longer period of time. His is perhaps a more pragmatic and less dazzling mind, but he saw all the dangers of the 2003 move into Iraq, argued against the invasion, and for his troubles was dismissed as chairman of the prestigious President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board.

I. The Truman Analogy

Recently, Harry Truman, for reasons that would surely puzzle him if he were still alive, has become the Republicans' favorite Democratic president. In fact, the men around Bush who attempt to feed the White House line to journalists have begun to talk about the current president as a latter-day Truman: Yes, goes the line, Truman's rise to an ever more elevated status in the presidential pantheon is all ex post facto, conferred by historians long after he left office a beleaguered man, his poll numbers hopelessly low. Thus Bush and the people around him predict that a similar Trumanization will ride to the rescue for them.

I've been living with Truman on and off for the last five years, while I was writing a book on the Korean War, The Coldest Winter [to be published in September by Hyperion], and I've been thinking a lot about the differences between Truman and Bush and their respective wars, Korea and Iraq. Yes, like Bush, Truman was embattled, and, yes, his popularity had plummeted at the end of his presidency, and, yes, he governed during an increasingly unpopular war. But the similarities end there.

Even before Truman sent troops to Korea, in 1950, the national political mood was toxic. The Republicans had lost five presidential elections in a row, and Truman was under fierce partisan assault from the Republican far right, which felt marginalized even within its own party. It seized on the dubious issue of Communist subversion—especially with regard to China—as a way of getting even. (Knowing how ideological both Bush and Cheney are, it is easy to envision them as harsh critics of Truman at that moment.)

Truman had inherited General Douglas MacArthur, "an untouchable," in Dwight Eisenhower's shrewd estimate, a man who was by then as much myth and legend as he was flesh and blood. The mastermind of America's victory in the Pacific, MacArthur was unquestionably talented, but also vainglorious, highly political, and partisan. Truman had twice invited him to come home from Japan, where, as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, he was supervising the reconstruction, to meet with him and address a joint session of Congress. Twice MacArthur turned him down, although a presidential invitation is really an order. MacArthur was saving his homecoming, it was clear, for a more dramatic moment, one that might just have been connected to a presidential run. He not only looked down on Truman personally, he never really accepted the primacy of the president in the constitutional hierarchy. For a president trying to govern during an extremely difficult moment in international politics, it was a monstrous political equation.

Truman had been forced into the Korean War in 1950 when the Chinese authorized the North Koreans to cross the 38th parallel and attack South Korea. But MacArthur did not accept the president's vision of a limited war in Korea, and argued instead for a larger one with the Chinese. Truman wanted none of that. He might have been the last American president who did not graduate from college, but he was quite possibly our best-read modern president. History was always with him. With MacArthur pushing for a wider war with China, Truman liked to quote Napoleon, writing about his disastrous Russian adventure: "I beat them in every battle, but it does not get me anywhere."

In time, MacArthur made an all-out frontal challenge to Truman, criticizing him to the press, almost daring the president to get rid of him. Knowing that the general had title to the flag and to the emotions of the country, while he himself merely had title to the Constitution, Truman nonetheless fired him. It was a grave constitutional crisis—nothing less than the concept of civilian control of the military was at stake. If there was an irony to this, it was that MacArthur and his journalistic boosters, such as Time-magazine owner Henry Luce, always saw Truman as the little man and MacArthur as the big man. ("MacArthur," wrote Time at the moment of the firing, "was the personification of the big man, with the many admirers who look to a great man for leadership.… Truman was almost a professional little man.") But it was Truman's decision to meet MacArthur's challenge, even though he surely knew he would be the short-term loser, that has elevated his presidential stock.

George W. Bush's relationship with his military commander was precisely the opposite. He dealt with the ever so malleable General Tommy Franks, a man, Presidential Medal of Freedom or no, who is still having a difficult time explaining to his peers in the military how Iraq happened, and how he agreed to so large a military undertaking with so small a force. It was the president, not the military or the public, who wanted the Iraq war, and Bush used the extra leverage granted him by 9/11 to get it. His people skillfully manipulated the intelligence in order to make the war seem necessary, and they snookered the military on force levels and the American public on the cost of it all. The key operative in all this was clearly Vice President Cheney, supremely arrogant, the most skilled of bureaucrats, seemingly the toughest tough guy of them all, but eventually revealed as a man who knew nothing of the country he wanted to invade and what that invasion might provoke.

II. The New Red-Baiting

If Bush takes his cues from anyone in the Truman era, it is not Truman but the Republican far right. This can be seen clearly from one of his history lessons, a speech the president gave on a visit to Riga, Latvia, in May 2005, when, in order to justify the Iraq intervention, he cited Yalta, the 1945 summit at which Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill met. Hailing Latvian freedom, Bush took a side shot at Roosevelt (and, whether he meant to or not, at Churchill, supposedly his great hero) and the Yalta accords, which effectively ceded Eastern Europe to the Soviets. Yalta, he said, "followed in the unjust tradition of Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Once again, when powerful governments negotiated, the freedom of small nations was somehow expendable. Yet this attempt to sacrifice freedom for the sake of stability left a continent divided and unstable. The captivity of millions in Central and Eastern Europe will be remembered as one of the greatest wrongs of history."

This is some statement. Yalta is connected first to the Munich Agreement of 1938 (in which the Western democracies, at their most vulnerable and well behind the curve of military preparedness, ceded Czechoslovakia to Hitler), then, in the same breath, Bush blends in seamlessly (and sleazily) the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the temporary and cynical agreement between the Soviets and Nazis allowing the Germans to invade Poland and the Soviets to move into the Baltic nations. And from Molotov-Ribbentrop we jump ahead to Yalta itself, where, Bush implies, the two great leaders of the West casually sat by and gave away vast parts of Europe to the Soviet Union.

After some 60 years Yalta has largely slipped from our political vocabulary, but for a time it was one of the great buzzwords in American politics, the first shot across the bow by the Republican right in their long, venomous, immensely destructive assault upon Roosevelt (albeit posthumously), Truman, and the Democratic Party as soft on Communism—just as today's White House attacks Democrats and other critics for being soft on terrorism, less patriotic, defeatists, underminers of the true strength of our country. Crucial to the right's exploitation of Yalta was the idea of a tired, sick, and left-leaning Roosevelt having given away too much and betraying the people of Eastern Europe, who, as a result, had to live under the brutal Soviet thumb—a distortion of history that resonated greatly with the many Eastern European ethnic groups in America, whose people, blue-collar workers, most of them, had voted solidly Democratic.

The right got away with it, because, of all the fronts in the Second World War, the one least known in this country—our interest tends to disappear for those battles in which we did not participate—is ironically the most important: the Eastern Front, where the battle between the Germans and Russians took place and where, essentially, the outcome of the war was decided. It began with a classic act of hubris—Hitler's invasion of Russia, in June 1941, three years before we landed our troops in Normandy. Some three million German troops were involved in the attack, and in the early months the penetrations were quick and decisive. Minsk was quickly taken, the Germans crossed the Dnieper by July 10, and Smolensk fell shortly after. Some 700,000 men of the Red Army, its leadership already devastated by the madness of Stalin's purges, were captured by mid-September 1941. The Russian troops fell back and moved as much of their industry back east as they could. Then, slowly, the Russian lines stiffened, and the Germans, their supply lines too far extended, faltered as winter came on. The turning point was the Battle of Stalingrad, which began in late August 1942. It proved to be the most brutal battle of the war, with as many as two million combatants on both sides killed and wounded, but in the end the Russians held the city and captured what remained of the German Army there.

In early 1943, the Red Army was on the offensive, the Germans in full retreat. By the middle of 1944, the Russians had 120 divisions driving west, some 2.3 million troops against an increasingly exhausted German Army of 800,000. By mid-July 1944, as the Allies were still trying to break out of the Normandy hedgerows, the Red Army was at the old Polish-Russian border. By the time of Yalta, they were closing in on Berlin. A month earlier, in January 1945, Churchill had acknowledged the inability of the West to limit the Soviet reach into much of Eastern and Central Europe. "Make no mistake, all the Balkans, except Greece, are going to be Bolshevized, and there is nothing I can do to prevent it. There is nothing I can do for Poland either."

Yalta reflected not a sellout but a fait accompli.

President Bush lives in a world where in effect it is always the summer of 1945, the Allies have just defeated the Axis, and a world filled with darkness for some six years has been rescued by a new and optimistic democracy, on its way to becoming a superpower. His is a world where other nations admire America or damned well ought to, and America is always right, always on the side of good, in a world of evil, and it's just a matter of getting the rest of the world to understand this. One of Bush's favorite conceits, used repeatedly in his speeches, is that democracies are peaceful and don't go to war against one another. Most citizens of the West tend to accept this view without question, but that is not how most of Africa, Asia, South America, and the Middle East, having felt the burden of the white man's colonial rule for much of the past two centuries, see it. The non-Western world does not think of the West as a citadel of pacifism and generosity, and many people in the U.S. State Department and the different intelligence agencies (and even the military) understand the resentments and suspicions of our intentions that exist in those regions. We are, you might say, fighting the forces of history in Iraq—religious, cultural, social, and inevitably political—created over centuries of conflict and oppressive rule.

The president tends to drop off in his history lessons after World War II, especially when we get to Vietnam and things get a bit murkier. Had he made any serious study of our involvement there, he might have learned that the sheer ferocity of our firepower created enemies of people who were until then on the sidelines, thereby doing our enemies' recruiting for them. And still, today, our inability to concentrate such "shock and awe" on precisely whom we would like—causing what is now called collateral killing—creates a growing resentment among civilians, who may decide that whatever values we bring are not in the end worth it, because we have also brought too much killing and destruction to their country. The French fought in Vietnam before us, and when a French patrol went through a village, the Vietminh would on occasion kill a single French soldier, knowing that the French in a fury would retaliate by wiping out half the village—in effect, the Vietminh were baiting the trap for collateral killing.

III. The Perils of Empire

You don't hear other members of the current administration citing the lessons of Vietnam much, either, especially Cheney and Karl Rove, both of them gifted at working the bureaucracy for short-range political benefits, both highly partisan and manipulative, both unspeakably narrow and largely uninterested in understanding and learning about the larger world. As Joan Didion pointed out in her brilliant essay on Cheney in The New York Review of Books, it was Rumsfeld and Cheney who explained to Henry Kissinger, not usually slow on the draw when it came to the political impact of foreign policy, that Vietnam was likely to create a vast political backlash against the liberal McGovern forces. The two, relatively junior operators back then, were interested less in what had gone wrong in Vietnam than in getting some political benefit out of it. Cheney still speaks of Vietnam as a noble rather than a tragic endeavor, not that he felt at the time—with his five military deferments—that he needed to be part of that nobility.

Still, it is hard for me to believe that anyone who knew anything about Vietnam, or for that matter the Algerian war, which directly followed Indochina for the French, couldn't see that going into Iraq was, in effect, punching our fist into the largest hornet's nest in the world. As in Vietnam, our military superiority is neutralized by political vulnerabilities. The borders are wide open. We operate quite predictably on marginal military intelligence. The adversary knows exactly where we are at all times, as we do not know where he is. Their weaponry fits an asymmetrical war, and they have the capacity to blend into the daily flow of Iraqi life, as we cannot. Our allies—the good Iraqi people the president likes to talk about—appear to be more and more ambivalent about the idea of a Christian, Caucasian liberation, and they do not seem to share many of our geopolitical goals.

The book that brought me to history some 53 years ago, when I was a junior in college, was Cecil Woodham-Smith's wondrous The Reason Why, the story of why the Light Brigade marched into the Valley of Death, to be senselessly slaughtered, in the Crimean War. It is a tale of such folly and incompetence in leadership (then, in the British military, a man could buy the command of a regiment) that it is not just the story of a battle but an indictment of the entire British Empire. It is a story from the past we read again and again, that the most dangerous time for any nation may be that moment in its history when things are going unusually well, because its leaders become carried away with hubris and a sense of entitlement cloaked as rectitude. The arrogance of power, Senator William Fulbright called it during the Vietnam years.

I have my own sense that this is what went wrong in the current administration, not just in the immediate miscalculation of Iraq but in the larger sense of misreading the historical moment we now live in. It is that the president and the men around him—most particularly the vice president—simply misunderstood what the collapse of the Soviet empire meant for America in national-security terms. Rumsfeld and Cheney are genuine triumphalists. Steeped in the culture of the Cold War and the benefits it always presented to their side in domestic political terms, they genuinely believed that we were infinitely more powerful as a nation throughout the world once the Soviet empire collapsed. Which we both were and very much were not. Certainly, the great obsessive struggle with the threat of a comparable superpower was removed, but that threat had probably been in decline in real terms for well more than 30 years, after the high-water mark of the Cuban missile crisis, in 1962. During the 80s, as advanced computer technology became increasingly important in defense apparatuses, and as the failures in the Russian economy had greater impact on that country's military capacity, the gap between us and the Soviets dramatically and continuously widened. The Soviets had become, at the end, as West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt liked to say, Upper Volta with missiles.

At the time of the collapse of Communism, I thought there was far too much talk in America about how we had won the Cold War, rather than about how the Soviet Union, whose economy never worked, simply had imploded. I was never that comfortable with the idea that we as a nation had won, or that it was a personal victory for Ronald Reagan. To the degree that there was credit to be handed out, I thought it should go to those people in the satellite nations who had never lost faith in the cause of freedom and had endured year after year in difficult times under the Soviet thumb. If any Americans deserved credit, I thought it should be Truman and his advisers—Marshall, Kennan, Dean Acheson, and Chip Bohlen—all of them harshly attacked at one time or another by the Republican right for being soft on Communism. (The right tried particularly hard to block Eisenhower's nomination of Bohlen as ambassador to Moscow, in 1953, because he had been at Yalta.)

After the Soviet Union fell, we were at once more powerful and, curiously, less so, because our military might was less applicable against the new, very different kind of threat that now existed in the world. Yet we stayed with the norms of the Cold War long after any genuine threat from it had receded, in no small part because our domestic politics were still keyed to it. At the same time, the checks and balances imposed on us by the Cold War were gone, the restraints fewer, and the temptations to misuse our power greater. What we neglected to consider was a warning from those who had gone before us—that there was, at moments like this, a historic temptation for nations to overreach.

David Halberstam was a Vanity Fair contributing editor and the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Best and the Brightest and The Fifties. He was killed in a car accident on April 23.